A highlight of pre-Covid years was always the annual Citywire New Model Adviser Conference in London. I first attended this flagship event in 2014 but until now I hadn’t realised the extent to which it has helped connect me with new ideas and the views of others in our amazingly multi-faceted profession.

Having not attended for two years, it was truly wonderful to be able to break the awful habit of professional isolation and connect with real people in person once again, something we may soon come to refer to as a ‘post-Covid-out-of-Zoom-experience’.

For two days, I reconnected with peers and with London. I ran the Westminster to Chelsea Thames circuit on Thursday evening and attended some of the most amazing presentations from internationally renowned thinkers on subjects from neuroscience to slavery.

A mole at the Foreign Office

Thursday morning began with a keynote speech from the BBC’s media editor, Amol Rajan, discussing digital media and online publishing. He opened by explaining that his name is pronounced ‘A Mole’ not ‘Amol’ and that we could best remember the correct pronunciation by thinking what we would say if we one day saw a mole: “Oh look! It’s a mole!”.

He recounted that when he worked as an adviser at the Foreign Office, when phoning people he would say, “this is Amol at the Foreign Office,” which was sometimes answered with, “why would you be telling us this?”.

His talk focused brilliantly on the link between what he described as “two seemingly disparate interests” of his: “on the one hand, this epochal moment we’re living through and on the other hand, what is mischaracterised as social mobility, via a connective tissue which is our decaying democracy”.

It was an intriguing start to what turned out to be truly illuminating journey through the turmoil of our current political, media focused, conflict ridden world and class dominated, socially immobile, country. It seems something of a cop-out not to recount in detail his entire speech now, but I may report back to you on Amol’s views another day because they were fascinating.

On the hunt for new funds

Between the keynote speakers, we attended fund manager meetings, where a wide variety of fund managers presented their investment ideas to small groups in short 30 minute board room style seminars.

I am always on the hunt for new funds to populate the Key to the Future portfolio, and possibly replace funds when they reach the end of their shelf life with us. The rotation from ‘growth’ to ‘value’ is something I’ve mentioned in the past, and finding funds that are sustainable, impactful and operate a value-based investment philosophy is no mean task.

So, my objective at the conference was to quiz fund managers on this and attempt to come up with new ideas. It’s interesting how questions can sometimes reveal unexpected results.

Despite being ostensibly highly competitive, the investment management world is surreptitiously collaborative, in a way that many professions can be at a peer group level. Managers quite often interact with other managers from other firms and readily offer useful insights in face-to-face meetings, long before you ‘read all about it’ in the press.

An authority on the subject of racism

The after-lunch keynote delivered an uncomfortable truth. Professor of Public History at the University of Manchester, David Olusoga OBE, spoke of the link between history and modern society and the lasting influence of the British empire on our modern views and attitudes towards people of colour.

Despite being well argued, evidenced and full of compelling facts, sadly and perhaps predictably, the presentation was all too much for a number of racists in the audience. Several people walked out, and one delegate made a complete fool of himself trying to argue that all Professor Olusoga had achieved by raising the question of Britain’s involvement in the slave trade, was to antagonise and upset people.

The professor’s response was devastating and brilliantly executed. Some people need more than a ladder when they’re in a hole and, despite offers to take his shovel away, the antagonist kept on digging until his humiliation was complete.

It’s worth remembering that David Olusoga is a former BBC Radio 4 researcher and was involved in producing and directing historical documentaries there. His programmes included Namibia: Genocide and the Second Reich, The Lost Pictures of Eugene Smith, and Abraham Lincoln: Saint or Sinner?

He then became a presenter of documentaries including Civilisations, The World’s War: Forgotten Soldiers of Empire and the BAFTA award winning Britain’s Forgotten Slave Owners. He has also written many books including The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism. So, it’s fair to say that he is an authority on the subject of racism.

Olusoga’s TV series Black & British: A Forgotten History, examined how the foundations and continued economic success of Britain’s global empire and the Industrial Revolution were built on the phenomenally successful economic model of slavery.

The overriding theme of the professor’s keynote was ‘forgotten history’. We are educationally, emotionally, and culturally manipulated to be ignorant of our true history and its meaning in our current era.

The overpowering connection between what was believed in early colonial Britain and Europe, about the intelligence and abilities of non-white human beings – mostly Arabs, Africans and Asians – is forgotten to the extent that the truth is simply buried. It was uncomfortable to hear.

The times, they are a-changing

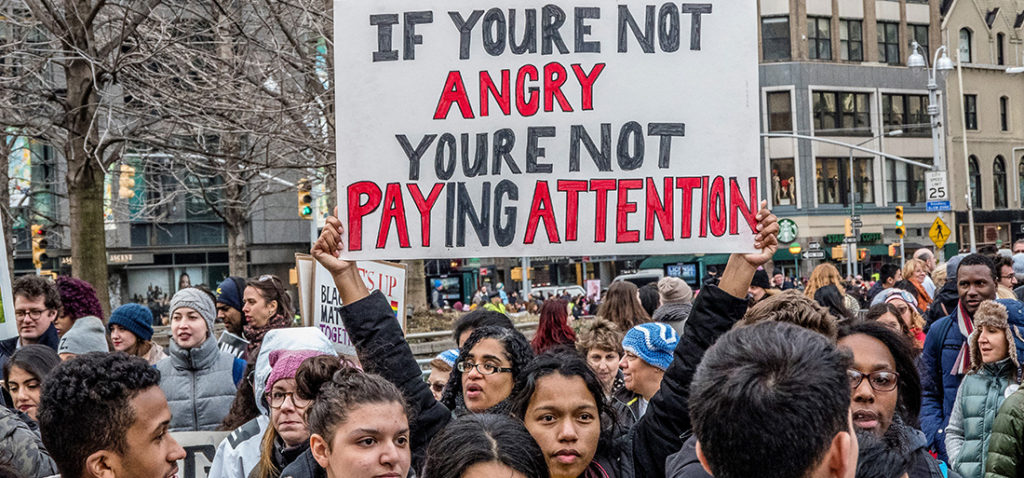

The extent to which modern and successful European economies, including our own, are based on this has been massively understated. As a nation, it’s only recently that some people have had the courage to confront our troubling past, and this is leading to an uncomfortable divide between the younger and the somewhat older generations.

Previously, divisions have largely been based on standards of living, music, and pop culture. Racial inequality and racism – whether internalised, interpersonal, or institutional – have until now been subjects that many have felt unable to openly debate and challenge, without a degree of discomfort. That is changing.

Professor Olusoga spoke about the current generation of young undergraduates who now have the information and the willingness to understand our past in a way that is both challenging and sympathetic.

Sympathy is not to condone any level of racism or historic ignorance wilful or inadvertent, but it is necessary to prevent a painful rift between the generations. It recognises that most of us do have views that are inconsistent with the facts. Due to inadequate information from our educations which only told us half of the story, many of us older folk know a version of history that bears little relationship to the truth.

David Olusoga argued that a step change was occurring in the current generation of undergraduates in all disciplines and that, in the years to come, all generations will understand our history differently without being overly judgemental and consequently they will be able to view race very differently.

A mental strength specialist

The day ended with what turned out to be a surprisingly emotional and inspiring talk from Penny Mallory, former champion rally driver and the only woman to have driven for the Ford World Rally Team.

Penny’s story shows that from impossibly difficult beginnings it is possible to do the seemingly impossible. She left home aged 14 and lived rough for years until, following the death of her boyfriend from an overdose, she managed to pull her life together. Eventually, she was able to follow her childhood dream to become a rally driver.

Since then, she’s been a TV presenter on the precursor to Top Gear and is now a mental strength specialist working with F1 teams and others in motorsport. I think most people were left with the impression that – although she is clearly a most extraordinary and outwardly inspiring individual – somehow, she still doesn’t believe her own success.

As the sports psychologist Steve Peters says, there is a part of our brain that needs to be controlled because it is always urging us to the next challenge before we have had a chance to reflect on and celebrate the success that we have already achieved, leaving us less happy than we should be considering how amazing we really are in the eyes of others.

Penny gave me the impression of someone who is unjustifiably scared off slowing down or stopping in case they fall off the bike and all their achievements come crashing down around them. If this is true, then it’s a real shame but it would be understandable given the enormous challenges she has overcome, particularly being a highly successful woman in a very male-dominated sport.

The Science of Fate

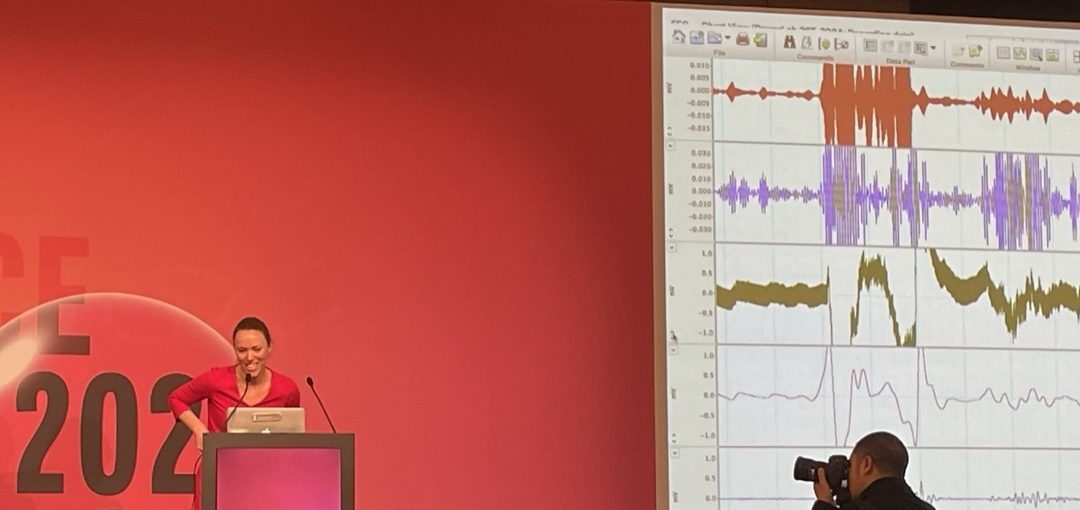

Dr Hannah Critchlow is a leading neuroscientist specialising in cellular and molecular neuroscience. She opened day two with an exciting interactive session that involved wiring up a financial adviser and showing everyone graphically what he was thinking!

Her description of his brain as ‘wonderful and beautiful’ had a very pronounced effect on his brainwave chart as you can see in the photograph. I wasn’t brave enough to volunteer but I did buy her book The Science of Fate when I was waiting for my train at Waterloo that afternoon.

Dr Critchlow’s theory is that we don’t have a lot of free will. Her research suggests that who we are is largely inherited at birth. Our decisions, beliefs and attitudes are massively influenced by the way in which our brain develops, often literally plotting our futures!

Connection across the conference

It’s a bit disappointing to discover how little we are able to determine our fate but, in many ways, it made a lot of sense and linked rather nicely to what we’d learned from the previous speakers.

Amol Ragan spoke about the difficulties of meaningful social mobility. David Olusoga’s forgotten histories, and the way we think about race, gains even more traction with an understanding of the neuroscience that underlies the development of our thoughts and attitudes. Penny Mallory’s mental toughness also seemed to me to be closely related to much of the work done by Hannah Critchlow.

This level of connection across the conference was thought provoking.